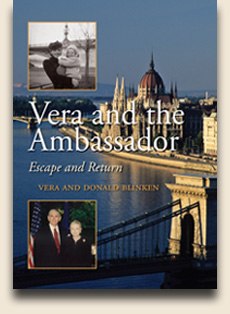

A Conversation with Vera and Donald Blinken

Donald, what were the pros and cons of being a non-career diplomat after building a successful career as an investment banker in New York City?

Unfamiliarity with State Department personnel and procedures sometimes makes it difficult to navigate State Department practices.

The pros are considerable.

First, the political appointees bring a range of valuable experiences from the private sector. Second, he or she can make difficult decisions based purely on the merits, and take actions rather than avoid doing so for fear of hindering a career advancement. Third, non-career ambassadors have relationships with the White House, giving them the opportunity to explore new ideas and directions outside the constraints of State Department bureaucracy.

In my experience, I have found that a mix of career and political appointees benefits our diplomacy.

Why was it so significant for you to be ambassador to Hungary, and only Hungary?

I was confident that Hungary was the right place for us. Vera and I had the perfect qualifications and commitment to be able to make a significant contribution. I knew that Vera’s Hungarian background, her fluency in the language, and our already established contacts there, as well as my experience in investment banking and public service as Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the State University of New York, were uniquely strong credentials for the appointment.

What were some of the most difficult challenges you were faced with in navigating this post Cold War former Soviet Satellite?

The most difficult challenge was the understandable cynicism of the Hungarian people and their government after more than 40 years of communist and Soviet domination. My task was to persuade them that there was no hidden agenda behind my counsel and actions. The United States was committed to helping Hungary become a partner in a democratic and free Europe. The advice we gave was aimed at achieving this goal.

I was also faced with the on-going historical tensions between Hungary and two of its neighbors—Romania and Slovakia. The 1920 Treaty of Trianon left two million ethnic Hungarians in what became Romania, and 600,000 in Slovakia.

What is your most treasured memory from your time as an ambassador to Hungary?

My proudest moment occurred on November 28, 1995, when I informed Washington that the Hungarian Parliament, by a vote of 312 to 1, committed Hungary to provide support for the NATO Bosnian peacekeeping mission by accepting the presence of NATO troops only four years after the last Soviet soldiers left Hungarian soil. The vote also paved the way for Hungary to be invited to join NATO. In November 1997, the Hungarian people overwhelmingly ratified a referendum supporting NATO membership.

Vera, you were born in Budapest and escaped with your mother to America as a girl in 1950. How did you view America, and was the transition very difficult for you?

Before I arrived in New York, my only knowledge of America was from a photograph of Niagara Falls, because the Soviet occupation of Hungary after World War II had closed the country off from the West. I wanted to become 200% American so I quickly learned to speak English.

What was it like for you to return to your native Hungary with Donald for his ambassadorship?

I had been going to Hungary regularly since 1987 when I created a foundation to improve Hungarian nutrition and to promote cultural exchanges between Hungary and the United States.

So it was very moving for me to return in 1994, as the wife of the American Ambassador, and exciting to become Donald’s 24/7 in-house interpreter.

You worked to create the first mobile mammography program in Hungary, called PRIMAVERA. What motivated you to take such a proactive role in spreading breast cancer screening among Hungarian women?

I initiated a women’s group of professional Hungarian women to volunteer their time, expertise and contacts for networking and public service, neither of which were practiced during the Soviet occupation of the previous 45 years. Searching for a project that would be of interest to all members of our group, I identified the need for access to mammography and the early detection of breast cancer, for women in small towns and villages where the necessary equipment for this life-saving procedure was not available. PRIMAVERA was the first such program, not only in Hungary, but in Central and Eastern Europe.

In the book you candidly describe your role in the ambassadorial residence, managing everything from the décor of the residence to the kitchen and wait staff. What was the most challenging for you?

By far, the most difficult challenge was to teach the Hungarian staff, not used to extending hospitality under the previous Communist regime, to treat our guests in a friendly and welcoming manner. I could readily teach them to set a beautiful table and to serve properly, but it was much harder to get them to smile. Eventually they did, and enjoyed doing so.

Your book is also a great love story. How did your shared experiences in Hungary affect your relationship with Donald?

Because we were far away from the support of family and friends and had to rely on each other more than ever, our experience in Hungary bonded us even closer to each other. Our open secret is that we love and respect each other. We complement and support each other without ever competing, thus bringing out the best in each of us.