ESCAPE

Run, Vera, run! Run as fast as you can!” I was ten years old. On that moonless night, Mother and I had traveled on a train to a bleak station far from our Budapest home and were now running through thick, dark woods.

“Faster, Vera!” she kept urging. “Faster!”

I ran as fast as I could over barely visible roots and around shadowy tree trunks. For what reason, I had no idea.

Only later did Mother explain. Like so many Hungarians before us, we were trying to escape by running through the woods and jumping onto the train after it passed passport control, slowing down around a curve before continuing into Austria and freedom. But I could not run fast enough. We could not catch up to the train and were left behind; so we had to go back to Budapest. I knew it was all my fault.

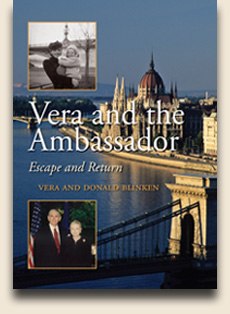

Now, more than four decades later, it seemed like a dream as we stood alongside Secretary of State Warren Christopher on a cold, gray, cloudy December morning in 1994. I was back in Budapest, standing on the tarmac of Ferihegy Airport with my husband, Donald Blinken, the United States Ambassador to the Republic of Hungary. We were awaiting the arrival of President Bill Clinton aboard Air Force One. Just five years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, historic changes were sweeping across Hungary and other former communist countries in Eastern Europe.

Heavy cloud cover enveloped the airport. Soon, far in the distance, we heard the thunderous rumbling of a jet approaching and, a short time later, the loud squeal of airplane tires touching down. Even on the ground, visibility was poor and we couldn’t quite make out the jumbo jet. A few moments later, a gleaming white airliner appeared out of the grayness and slowly taxied toward us. The large black letters on its side proclaimed: United States of America.

This stunning and dramatic vision made me feel like a character in a novel. Only this was real, as Donald kept reminding me, and welcoming President Clinton as his ambassadorial husband-and-wife team in Hungary was the culmination of our uncommon journey. How had that frightened little girl trying to escape Soviet-occupied Hungary come to find herself in such a place?

BUDAPEST

My return to Hungary took many turns, and begins with my mother, Lili. The youngest of three sisters, she was vivacious, outgoing, and lovable. She had blonde hair and the most beautiful bright blue eyes that sparkled whenever she laughed, which was often. She was thin and petite, 5-feet 4-inches in heels. Her first husband died in an automobile accident after one year of marriage; left with few resources, she supported herself by giving French lessons. Her charming personality soon caused two men to fall in love with her: Jozsef Ermer and Paul Flesch. Jozsef was a banker of medium height, with brown hair and blue eyes; his demeanor was formal and serious, hiding a keen sense of humor. Paul was the son of a rural veterinarian who yearned to be a doctor. He was unusually tall for a Hungarian, six feet, three inches, a gentle giant of a man. When laws were passed prohibiting Jews from attending medical school, Paul went to Austria, learned German, completed medical school, and passed his qualifying exams. Upon returning to Hungary and passing the exams again, this time in Hungarian, he began an internship in pediatrics.

Lili chose to marry Jozsef and was determined to have a child. With war threatening to erupt in Europe, her cautious husband thought the times were too dangerous to bring a child into the world. Fortunately for me, Lili got her way. Her marriage to Jozsef and my birth, along with the passage of anti-Jewish laws and Germany’s saber rattling, drove Paul to emigrate to America.

I was named Veronica but have always been called Vera because Mother thought it was a diminutive of Veronica. Actually, they are two entirely different names, and started my early duality. Mother loved me so much that she wanted to be everything to me. To prove how much she wanted me, she often recounted the exchange in which Father said this was not the time to bring another person into the world. I honestly believe she had no idea that she was inadvertently imparting the impression that Father didn’t want me, as if she had selected me beforehand and he had rejected the choice.

We were a happy little family in Budapest, but on March 19, 1944, life changed irrevocably. An infection behind my ear, which today would be cured by an antibiotic, had required the removal of the mastoid bone. While recovering at home after the surgery, I began to bleed through the bandages, and Mother quickly set off with me to the hospital. Our progress was suddenly blocked by crowds of people, and we saw regiments of German soldiers and armored vehicles moving in formation down the wide boulevard. For a child, frightened by the bleeding and unable to get to the hospital, this threat was very personal. Hungary had become part of the Axis Powers after Germany promised to restore the two-thirds of Hungarian territory lost after the 1920 Treaty of Trianon. Now, the Germans were occupying Budapest because they had discovered the Hungarian government was secretly negotiating with the Allies to switch sides.

On Christmas Eve, 1944, nine months after we watched the German Army enter our city, awareness of the war became inescapable even to a child. Mother and I were dressing for a family dinner to be held at her sister’s house in Buda, in the hilly, residential area across the Danube from our apartment in Pest. Father planned to meet us there. I had stubbornly insisted on wearing a favorite dress that was late coming back from a seamstress and, as a result, we were delayed leaving the apartment. Bypassing the heavily damaged Margit Bridge, closest to our home, we had almost reached the bridge to its north when planes suddenly attacked, killing everyone on it. We fled in terror. Mother’s hair soon turned white, and she always believed this was caused by the shock of our close call.

Soon afterwards, German authorities commandeered our Hollan Street apartment building and turned it into a temporary hospital. Father had not been able to cross the Danube and we had no idea where he was, yet we had to leave our home. By now, Pest was overcrowded with people fleeing from the countryside, all desperate for shelter from the fighting and the frigid cold. Somehow, my resourceful mother found an apartment at 2 Becsi Street, overlooking Erzsebet Square.

Mitzi, my nanny, was with us because her husband was in the Army. In her wonderful Teutonic way, Mitzi kept me very busy. It was a harshly cold winter and we had no heat, but the layers of clothes I wore at all times were no obstacle to Mitzi, who was always washing some part of me with very cold water, and saying, “The war will be over some day, and we have to make sure that when it is, this child will have good nails, good teeth, and good hair.” I bless her for that.

As the Germans retreated and the Allies advanced, the fighting reached Pest. Each block was fought for, each street became a battleground, and the fighting was house to house. There was looting, the stores were empty, and, like everyone else, we had no food left. As a last resort, Mother would run the few blocks from Becsi Street to the hotels along the Danube where food was sometimes still available. It was a very dangerous run, but she always took me with her. “If we are going to die,” she would say, “we are going to die together.” We lived with constant fear and hunger.

Later, deep into the siege, to keep us from starving, Mother began to interpret for the Germans in exchange for food. While interpreting, she would always ask, “Where are you coming from?” They replied with the name of one or another section or street in the city. In mid-January, a wounded German soldier said he had just come from the front.

“How far away is the front?” Mother asked.

“Erzsebet Square,” the soldier replied, and pointed to the street. The fighting was literally in front of our house.

Budapest was pounded by bombs almost daily and each time the sirens sounded, we had to rush to the basement, which had been turned into an air-raid shelter. We often had to spend long hours in those tight, dark quarters. A dim candle or two substituted for the electrical power that was an early casualty of the siege. Mother, Mitzi, and I had been assigned seats on benches along a wall; other occupants filled benches in the middle of the room. A typical little girl, I tired of sitting in the same place every day; so, on one occasion, a very nice older gentleman and two other kind people sitting next to him on a bench in the middle of the room offered to change places with us. Suddenly, a bomb struck the apartment house next door, setting it on fire and causing a wall in our building to collapse. Everybody sitting along that wall, where we had been sitting just moments earlier, died instantly.

We threw ourselves to the floor with our arms covering our heads as the rubble fell on us. Through a gaping hole in the wall and ceiling we could see the fire raging in the adjacent building. All the adults knew that the Germans were using the building behind ours as an ammunition depot. If the fire reached it, the whole block would blow up. We were desperate to find a way out, but mounds of debris blocked us, and we thought we would soon die. Miraculously, a heavy snow began to fall, putting out the fire. The snowstorm and a child’s whim had saved our lives, but three people had died for doing something nice for a little girl.

On January 16, 1945, Soviet soldiers entered our air raid shelter. They had come to liberate us, and one of the soldiers came over to shake my hand. Even stranger than his desire to shake the hand of a little girl were the wristwatches he wore all the way up his arm. Most of the Soviet advance soldiers were from rural areas, had never seen wristwatches before, and didn’t know that they had to be wound. Whenever a watch stopped, they threw it away and grabbed some more. Meanwhile, the Germans had retreated over the remaining bridges into Buda and then blown them up. The battle would continue on the Buda side for another month, until the Soviets finally overran the last Germans, who were holding out in the royal castle on the hill above the city.

What the Soviets would do afterward to Hungary and the other countries of the region was tragic, but in those first days we were grateful to them for reaching us before we died. Unaware of what the future held, at that moment we truly felt liberated. After our liberation from the Germans, Mother’s first thought was to search for Father. She assumed that he had been caught on the Buda side on Christmas Eve. Thinking his brother might know where he was, Mother dressed us both in all the clothes we had to protect us from the terrible cold, and we ventured outside to find my uncle.

We found the city in ruins. Many buildings were only heaps of brick, stone, and plaster, and every window was shattered. In front of one building rows of dead bodies were piled up. The building had been a holding center for Jews awaiting deportation. Before retreating, with no time to ship them to concentration camps, the Germans shot their captives and stacked the corpses outside. As Mother and I walked on, I bumped into someone I thought was sprawled in the street. He failed to respond when I excused myself.

“He is not very polite,” I told Mother. “He didn’t say anything.”

“He can’t,” Mother replied. “He is dead.”

We walked on and saw people crowded around a dead horse. They were carving it up for food.

To our great joy and relief, we found Father at my uncle’s apartment. He had indeed been caught on the Buda side, but later walked across the frozen Danube to look for us at home. Nobody knew where we had gone, so he went to his brother’s apartment. Only six blocks away from us during the siege, he might have been in a different country until the Soviets fought their way from his street to ours. He and my uncle had somehow acquired a single, extraordinary food supply: a very large sack filled with chunks of white sugar. This was the first nourishment Mother and I had eaten in several days. Not very good for the teeth, but we were overjoyed to have it. That sack of sugar would sustain us for quite some time, and to this day, I always have at least ten pounds of sugar at home—just in case.

My parents and I started back toward our old apartment in a heavy snowstorm. Beside me on a child’s sled were our few possessions. Father pulled the sled along Szent Istvan Avenue, a once-grand boulevard now dark and heavily damaged. Not a single vehicle was on it, just people like us walking or pulling children and belongings on sleds. Mother had been deprived of cigarettes during the war, but had now located a few and wanted to stop for a smoke. Father put the rope down and courteously went over to light her cigarette. At that instant, a stray bullet whistled down through the space where my father’s head had been a few seconds before. An act of providence had spared him. I still have that bullet.

Our apartment was miraculously undamaged, and its contents were mostly intact. We pushed most of the furniture back into place and tried to resume our lives. For the first night in weeks, although hungry, I went to sleep in my own bed in my corner room on the top floor of the six-story apartment building. A few hours later, the German bombers sounded overhead and then explosions rocked the city. One bomb struck the roof of our building, slicing off a corner of my ceiling. The bomb landed alongside the building without exploding. Heavy rain poured through the gaping hole in my bedroom, but I was alive. Earlier, my childish whims had kept us off a doomed bridge and away from a deadly wall collapse. Now, for the third time, I had been miraculously saved. Years would pass before I would begin to wonder why.

Whispers among survivors said the Soviets were savages, raping and murdering wherever they went. It was to our horror, therefore, that the next night several Soviet soldiers looking for a place to sleep chose our apartment. My mother’s perfume bottles had somehow survived the war. Perfume was another item most Russian soldiers had never seen before, and thinking it was a kind of whiskey, they drank it down. Of course, the perfume burned their throats terribly and they became enraged. Their anger threatened to turn violent, but they left us alone. Late that night, I peered through a keyhole into our living room, where the soldiers were sleeping on the floor with their guns beside them. It was a frightening sight.

The soldiers soon left our apartment in the morning and we were safe, but we were also very hungry. We had nothing to eat, and the only available food was in the countryside. Father feared being rounded up by the soldiers and sent to a Russian labor camp if he went outside, so Mother made her way to the country by train. Often the trains were so overcrowded that she was forced to cling to the roof of a rail car. As always, Mother showed remarkable ingenuity and courage.

The Hungarian Communists who had fled to Moscow after their failed coup at the end of World War I now came back to Budapest and took control of the government. Foreseeing that the end of the war would be followed by Soviet domination and repression, Mother urged Father to arrange our family’s emigration, which would have been possible just after the war. Not given to rash action, Father told her he thought the harsh times were only temporary. If things got really bad, with the help of his good friends and banking connections in Great Britain, we could escape to London. Soon, however, the government began to nationalize companies and financial institutions, among them father’s bank. He returned to join his brother at his family’s export-import company, where, on a cold winter day in 1947, Mother was visiting him when government officials entered.

“We will have your keys,” they said to Father.

Everyone knew what that meant. The company was being nationalized. Mother had already stopped wearing red nail polish, having been warned that the “bourgeois” color would bring undue attention. Now, when she went to put on her fur coat, an official said, “No, that stays, too.” Mother walked out into the freezing cold, knowing that her coat would end up on the shoulders of the man’s wife or girlfriend.

In 1948, the Communist Party openly took control of the government. All land was collectivized, industry was nationalized, and a “planned economy” was imposed. . . .

NEW YORK

I arrived at Vassar College six short years after leaving Communist Hungary. I did not own the de rigueur Bermuda shorts or buttondown shirts that everyone else was wearing, although I had several exquisite Pierre Cardin suits Aunt Manci had bought me in Paris. My European upbringing had not prepared me to live with girls who had attended prep schools and knew each other from country clubs; who carried themselves with an insider’s confidence I couldn’t begin to emulate. Once again, I felt totally out of place. My unhappiness and the resulting sleepless nights made me a prime target for that freshman bane, mononucleosis. By mid-October, I was back home, confined to bed and on my way to gaining twenty pounds. . . .

On October 23, 1956, my bedside radio brought the electrifying news that university students in Budapest were demonstrating for greater political freedom and the withdrawal of Soviet troops stationed on Hungarian soil. The uprising quickly spread to other regions and other segments of the population. Demands were made to liberalize all aspects of the oppressive political and economic systems. When the government’s security forces proved incapable of quelling the unrest, the Hungarian Army was called in, but the soldiers joined the revolt and distributed weapons to the insurgents. At the cost of many lives, Soviet troops were forced to withdraw beyond the country’s borders.

Freedom fighters took control of radio stations to keep the population informed and rally others to their cause. American-sponsored Radio Free Europe not only beamed information into the country but also, many would later contend, assurances that U.S. troops would come to the freedom fighters’ aid. Instead of sending in troops, the United States turned the matter over to the United Nations, and nothing was done.

On November 4, 1956, Soviet forces rolled back into Hungary to suppress the uprising. Behind the radio reporters’ voices I could hear the sounds of the uprising: guns firing, tanks rolling, and even Hungarian voices crying out, “They’re coming! They’re coming! This is our last broadcast.”

In the six years since leaving Hungary, as I was building a new life, I had not thought much about my childhood years. Now, I felt guilty. While I was safe in New York, young people my age—teenagers, college students, perhaps even former classmates—were engaged in gun battles and were throwing homemade Molotov cocktails at advancing Soviet tanks. Each day the uprising continued, my guilt increased: for not being there with my contemporaries, for having survived the war when thousands didn’t, for having escaped when millions couldn’t, and even for being alive when so many were now dying for their beliefs. I think it was at that point that the idea began to grow within me that there had to be a reason I had been saved when others perished, and perhaps even a reason for my being in America.

Twenty-seven hundred insurgents were killed in the fighting, and nineteen thousand were injured. Thousands of Hungarians were imprisoned, executed, or deported to Soviet labor camps, and during the ten days the borders were open, two hundred thousand Hungarians fled the country. Thanks to my indomitable Aunt Manci, our family was among them. Manci could treat a broken fingernail as a tragedy of vast proportions, but when serious action was called for, she rose to the occasion and acted gallantly. At the first report that the border was open, she rushed to Vienna and arranged to have someone drive a truck into Hungary and bring out the rest of our family still trapped in Budapest: my grandmother; Aunt Erzsike and her husband, Lajos; their architect son, Peter; Peter’s pregnant wife, Susan; and their young daughter, Ann. All but grandmother, who lived with us for the few remaining years of her life, emigrated to Canada. . . .

+ + +

With my business going well in the early 1970s, and my private life busy, if not happy, I began to feel a growing need to pay back the debt I owed God or fate for my good fortune. I was already doing interesting and useful volunteer work on the boards of arts organizations, but that was fun, not repayment. After doing some research, I found an organization to whose mission I related: The International Rescue Committee, which helped resettle refugees who had fled totalitarian regimes. If I hadn’t had an Aunt Manci, I might have been among them. The IRC was founded in 1933 at the suggestion of Albert Einstein to assist intellectuals fleeing Nazi Germany. Its founders hoped that after World War II ended, the IRC could be disbanded because the world would no longer have refugees. However, after the 1956 uprising opened Communist Hungary’s borders long enough for thousands of Hungarians to escape, it became sadly obvious that refugees would be fleeing totalitarianism for many decades to come. The IRC’s mission was still relevant. I informed the IRC that I would do anything to help—stuff envelopes or whatever was needed. In 1978 I was asked to join the board of directors, and the IRC has been an important part of my life ever since.

Despite my earlier resolve to become 200 percent American, I carry my past within me like every other refugee. This refugee mentality resurfaced during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. When war between the United States and the Soviet Union appeared imminent, Mother worriedly phoned and told me to go right out and stock up on sugar, and of course I immediately did. From our wartime experience, we knew that sugar would save us from starvation.

Mother often lamented my unmarried state, but I was in no hurry to wed and possibly make another mistake. My interior design business was going well and one day I phoned Mother to tell her that I had bought myself a mink coat. “Aren’t you proud of me, that I could do it on my own?” I asked.

Mother broke into tears. “No, no, no, a husband should buy you a fur coat.”

So, just to please Mother, on May 11, 1971, I went out on a blind date. It was with Donald Blinken. We had a very pleasant dinner at a neighborhood French restaurant, and the following morning I phoned two close friends and said, “I just met the man with whom I would like to spend the rest of my life. But it will take some time.”

Donald and I were married on October 15, 1975. I received a wedding band inscribed “D.B. to V.E. with all my love.” This simple gold band and my American passport are my two most treasured possessions. Donald’s son, Antony, who had been nine years old when we first met and was then thirteen, gave me the best possible wedding present when he told me how grateful he was to me for making his father so happy. And I am thankful for the close and loving relationship that Antony and I have continued.

Marriage to Donald provided me with emotional security for the first time in my life. I felt that our marriage was meant to be. My sense of security grew out of Donald’s genuine sincerity and his absolute reliability. “He’s like the Rock of Gibraltar,” I explained to my mother. Donald has a brilliant, complex mind, but he is admirably simple in this way: When he says something, he means it. When he says he will do something, he does it. That kind of reliability is very important to me, probably because of the uncertainty and turbulence of my childhood. In addition to our shared interests, we bring out the best in each other. We complement and support each other without competing.

Looking back, I can see that both of us came into our own and our horizons expanded after we married. I don’t think it was accidental that good and interesting things outside business began happening for Donald when I entered his life. His modesty causes him to downplay his accomplishments, but I have taken it upon myself to remind him how he shines at whatever he does. I hope that it was in part my unwavering belief in him and my encouragement that has provided Donald with a serenity that allowed him to take on new and exciting challenges. . . .

GETTING THINGS DONE

PREPARING FOR PEACE

We all felt a strong sense of duty and history as preparations for the Dayton Peace Accords in Bosnia got underway. On October 31, 1995, the presidents of Croatia, Bosnia, and Serbia (who also represented the Bosnian Serbs and whom Holbrooke insisted not get their own seat at the table) arrived at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, for the purpose of negotiating a permanent peace treaty. Everyone there understood that if the peace talks succeeded, the United States and other NATO countries would send in tens of thousands of troops to separate the warring sides. Gen. George Joulwan, the Supreme NATO Commander, was proposing a force of fifty to sixty thousand troops—one-third of whom would be American.

The potential danger to American and other NATO troops going into the war zone was very real. Already, more than one hundred U.N. peacekeepers had been killed trying to keep the peace. Two weeks before the start of the Dayton negotiations, Christopher, Perry, and Shalikashvili had appeared before the Senate Armed Services Committee. Both Democrats and Republicans voiced doubts about the wisdom of sending American troops into Bosnia, remembering the loss of life in Somalia and assuming casualties would occur on this new mission. The three administration officials tried to reassure the senators by saying that our troops would be out of Bosnia in twelve months—certainly an unrealistic estimate.

Formal negotiations to forge a peace agreement among the factions engaged in the horrific Bosnian-Croatian conflict began in Dayton on November 1, 1995. My own involvement in the process began early the next morning when Gen. William Crouch, commander in chief of the U.S. Army in Europe, entered my office at the embassy with a half-dozen top-ranking American military officers, including Lt. Gen. John Abrams, son of Gen. Creighton W. Abrams, Jr., the tank commander hero of World War II whose name graces the Abrams tank. I omitted the meeting from my printed daily schedule because the gathering was highly confidential. General Crouch had been purposely vague when requesting this meeting and would only go so far as to explain that it would deal with some aspect of NATO preparations for a peacekeeping force. We all understood that if the Dayton talks were successful, the NATO countries would have to act swiftly to send in thousands of troops to separate the warring sides. If the negotiations broke down, the less-than-adequate force of 12,500 U.N. peacekeepers already in the war zone would have to be pulled out as the fighting would almost certainly escalate.

I realized that these military leaders were under the strain of planning to send U.S. soldiers into harm’s way; I tried to soften the mood and break the ice at our first meeting by showing them a brass plaque commemorating the fifteen years that Cardinal Jozsef Mindszenty had been given sanctuary in the space that was now my office. I suggested that the cardinal, a man of immense courage, would have relished the sight of so many American military leaders, their shoulders spangled with stars and their chests resplendent with medals, convening here in a free Budapest for the purpose of imposing and maintaining in neighboring countries the peace and freedom that his beloved Hungary now enjoyed.

The generals waited until we moved to the secure, fourth-floor bubble before they began to discuss substantive issues. I began by giving the military officials a briefing on the current conditions in Hungary and was joined by DCM Jim Gadsden, our military attachés Army Colonel Arpad Szurgyi and Air Force Colonel Jon Martinson, as well as our political officers Bill Siefkin and Kurt Volker. I then turned over the meeting to General Crouch, who used detailed flip charts to explain the peacekeeping assignment in the war zone likely to be handed over to U.S. forces. Crouch also identified the U.S. military units that would be committed to the peacekeeping effort, or Implementation Force (IFOR), and their likely areas of deployment in Bosnia and Croatia, which were joined in a fragile federation at the time. We all understood the high stakes; this would be the largest deployment of U.S. forces in Europe since World War II. Central to this undertaking, we were told, would be the establishment of a staging area in close proximity to—but not within the borders of—Bosnia or Croatia. The key requirements for that staging area was a site with secure facilities, a safe environment, a dependable infrastructure of roads, rails, and airstrips, and genuine acceptance from and collaboration with the host government. The country that best met their criteria, they all concurred, was Hungary.

I watched General Crouch grow increasingly concerned as the briefing progressed, and he finally pushed aside his briefing book, looked me in the eyes, and got to the core of the matter with this blunt query: “Hungary is our first choice for an IFOR staging base. If President Clinton gives IFOR the green light, will you be willing and able to persuade the Hungarian government to let us base our troops in Hungary?”

All eyes in the room were riveted on me. General Crouch assured me he did not need an immediate answer; that I should take some time to ponder the question before answering it. He went on to express his concern that obtaining the Hungarian government’s approval might be a long and difficult process, with no guarantee that their cooperation would eventually be given.

I agreed with General Crouch’s assessment of the situation. Since coming to Budapest eighteen months earlier, I had worked steadily to gain the trust and acceptance of the Hungarian government and its people regarding the sincerity of the United States. The subtext of our discussion in the secure bubble was whether my efforts and those of my team would prove sufficient to overcome a number of major concerns that could derail the plan: Hungary’s memories of disappointments with the United States during the 1956 uprising; Hungary’s reticence to antagonize its ruthless neighbor, Serbia; concerns over possible retaliation against two hundred thousand ethnic Hungarians in northern Serbia; a military culture long linked to the Soviet Union; a natural aversion to allow foreign troops back onto its soil after recently ridding itself of the Russian army. As I weighed these considerations and calculated the odds, I felt that, despite more than a year of steady progress for preparing such a historic collaboration on peacekeeping forces, an uphill diplomatic struggle remained.

Clearly, I was staring down the most difficult and delicate decision of my diplomatic career. If my answer to General Crouch was an unqualified “yes” and the White House did decide to send U.S. troops into the former Yugoslavia, I would have committed myself to one of the most challenging and critical tests of diplomatic skill that an ambassador can face: obtaining permission from a host country for the entry and stationing of a large, heavily armed foreign military force. My nation’s leaders would rely on me to deliver not only the approval of a prime minister who had served at the highest levels of a former Communist enemy, but also a majority of the nearly four hundred members of Parliament, representing six contentious political parties, where extreme left-wing agitation against NATO and military involvement with the West was roiling the ranks. Furthermore, due to the urgency of the humanitarian mission, I would have to deliver in a matter of days, not months.

A favorable vote by Hungary’s National Assembly was no certainty, but all my instincts signaled I could obtain it. “General,” I replied, “when you’re ready to call on us officially to ask for Hungarian cooperation, consider it done!”

There was visible relief on the faces of the military men after my response. They left Budapest confident that they could count on the U.S. embassy’s unwavering and unconditional support, without which a Hungarian base for IFOR would have been impossible to obtain. To improve our chances of success, we did not wait for the peace treaty to be signed in Dayton. We got to work immediately. . . .

With no time to lose, I felt my strongest contribution would be cutting through bureaucratic delays and red tape. Fortunately, I found a like-minded Hungarian official willing to expedite matters, acting foreign minister Istvan Szent-Ivany. Young, Westernized, and decisive, he showed flexibility and initiative by agreeing that his government would proceed with the preparations for IFOR deployment without formal documentation, subject to Parliament’s approval of our request, which would be given fast track status. . . .

I sent a cable to Washington, an announcement that gave me the greatest personal satisfaction of my service as ambassador. It read:

Following consultations with the leaders of the six Parliamentary parties on the morning of November 27, the Parliamentary Defense Committee and the Foreign Affairs Committee met in an exceptional combined session at noon, November 27. The two committes approved the text of a Parliamentary resolution authorizing Hungary to provide support to IFOR. This resolution was then passed by the entire Parliament on the evening of November 28 by a vote of 312 in favor and 1 against it, with six abstentions. The resolution provides for the transit and temporary stationing of IFOR forces (not limited to U.S. forces) along with their equipment and supplies, as well as the use of Hungarian air space.

THE NATO VOTE

This was the rationale for voting for NATO membership that I made repeatedly to the Hungarian people: “For hundreds of years, you Hungarians have been unable to control your own destiny. You were controlled by the Turks, the Austrians, and the Soviets, but only briefly by yourselves. You made the wrong decisions before World War I and, consequently, lost a good deal of your territory. Unfortunately, when World War II came along, you were caught in the middle. You could not join the alliance against Germany because you were surrounded by the Germans, who finally invaded your country in 1944. And then you were occupied by the Russians. The NATO referendum next month will be the first time in four hundred years that you, the Hungarian people, are not being controlled by an outside force and can make a decision that affects your own destiny and future. It is a chance for you not to complain about the past, but to take some action about the future. You have the future in your own hands.”

We had a difficult task ahead of us because less than 40 percent of voters generally turn out for a referendum in Hungary. Mainly ardent opponents become motivated in these low-turnout votes. Could the pro-NATO faction put together a campaign that would overcome that traditional advantage for opponents? We chose to intensify our efforts to motivate the electorate to turn out and to vote for NATO membership. We organized meetings, printed literature, and planned ways of reaching the public, and I took every opportunity to give media interviews in favor of NATO membership.

I also had strong arguments for criticisms raised against joining NATO. Some critics complained that the cost would be too high. I explained that if Hungary did not join, it would have to face the unhappy prospect of modernizing its defense forces on its own and at its own expense. Hungarian leaders were concerned about a poor turnout; the lack of voters might indicate to Washington that the Hungarian people did not care enough about NATO security to go to the polls. If Hungarians did not care, why should the United States bear the expense of including Hungary in NATO, estimated at up to $33 billion over twelve years for Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic? I made sure that Hungarians understood that, as with their own government, the White House and the State Department had to make the case for NATO expansion to the U.S. Senate, which must, according to our Constitution, ratify treaties with foreign nations by a two-thirds vote.

Our extraordinary push for the NATO vote was derailed slightly by an article in the International Herald Tribune allegedly written by two British journalists who warned Hungarians not to vote for NATO because they had no guarantee the alliance would come to the country’s defense in case of attack. The article gained notoriety around Hungary and was discussed widely. When questioned by reporters, I said that it sounded like Russian propaganda and that every member of NATO received the same full support and defense.

The referendum took place on November 16, 1997. The next morning, Hungarians opened their newspapers to learn that more than 51 percent of the electorate had gone to the polls and nearly 75 percent of them had voted to join NATO. These were stunning numbers! It was a landslide victory, a bigger margin than any of us had predicted. We felt extra pride in the fact that the largest plurality came from the Taszar-Kaposvar area, where our NATO peacekeeping forces and community relations efforts had paid off. We celebrated our resounding victory, both for Hungary and for the efforts of our Embassy.